Arthur Miller's "Tragedy and the Common Man" was an eye opening piece for me because it introduced the idea of a "tragic flaw". Miller felt the "common man" was susceptible to tragedy to just as easily as "kings" were. Tragedy could apply to us all, because most common people fight their decline without grace. Miller argues that those who are "flawless" are only that way because they "accept their lot without retaliation". It's a concept I've never thought about, but since I'm writing this blog after reading Oedipus and Antigone I now see that their failures really just came from their failure to accept their own faults and fate. Miller also takes an approach that was foreign to me when he pointed out tragedy could in fact "imply more optimism...than...comedy". This was something I agreed with but somehow doesn't really fit into my philosophy of tragedy. I do see the optimism that can happen, but I don't see that in either Antigone or Oedipus. Perhaps had we looked at different pieces or more pieces I could see this parallel. Miller says this is a "misconception" but I'd rather say this is a misinterpretation of what Miller choses to view as right. If I've learned anything it is that tragedy is open subject for the reader to unfold and discover themselves. If you limit this, you limit what tragedy really means.

Antigone is the continuation of Oedipus the King that follows the story of Oedipus' daughter Antigone after his tragic descent from the throne. Her two brothers Eteocles and Polynices fought for Oedipus' throne and killed each other while doing so. Eteocles is given a proper burial but, by order of Kreon, Polynices is to remain untouched, unburied and left to rot. Anyone who disobeys this order will be killed, yet Antigone feels in her heart that she must give her brother the respect of a burial. This is Antigone's tragic misstep, for like her father she is blinded but this time by her passions that know no law. Tragedy is ever-present because Antigone fighting for what she finds just. I see nothing wrong with burying your family, and her points to me seem extremely valid. Even though her brothers were at odds they both reserve respect. I found comparison in this to modern day prisoners. Even the worst of serial killers are still buried. Heck, even Lee Harvey Oswald was buried honorably! Antigone's demise is tragic because she was just trying to give her loved ones honor. She was doing what the rest of Thebes was thinking too, making her even more of a tragic hero because she stood for more than one person in her firm ideals. Senator Wendy Davis of Texas stood suffering for hours to stand up for the women of her state and filibustering for 11 hours. Though it was not illegal, it was highly frowned upon by her Republican colleagues. People define Davis as "articulate and gutsy". This really doesn't differ from Antigone? She says "Go thine own way; myself will bury him." to Ismene. This is a firm unwavering statement. Antigone continues her declaration of goal by proclaiming "scorn...the eternal laws of heaven". She's dismissing her highest power in order to do what she feels is right, and what she feels Thebans would want too. Sen. Davis is like Antigone because they both stood up for something people supported but authority condemned. However, Davis was not met by the tragic fate Antigone was. By viewing Antigone through the lens of Sen. Davis we can see that her passion was her flaw that lead to Kreon ordering her death.

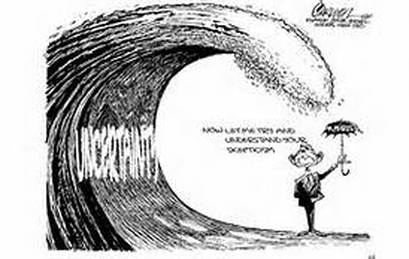

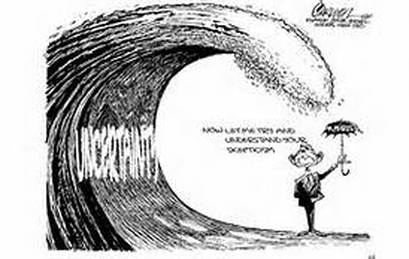

The Image: Uncertainty meeting a man holding an umbrella the reads "Hubris". He says" Now let me try and understand your skepticism" as the impending wave approaches him. The man appears to be quite pleased with himself despite his own demise being immanent. Why is this? I mean, the idea of being crushed should strike you with fear! Does he not see the wave, or does he choose to ignore it? He questions our doubt but it is clear the wave will crush him, there is no way out for him other than to be washed under. It's tragic that the man doesn't understand the gravity of his situation. He can't see past his own self assurance to see his umbrella of hubris won't protect him for long. Thus far, my own understanding of tragedy is that the great rise so high they overlook what could be their downfalls despite being warned. Their egos get the best of them. We saw this with Oedipus and his tragic realization of self. We saw this with Kreon when he failed to see that compassion was an option and lost his family in order to maintain his rule. These two men fell from grace when they felt they were at their peak. That seems like a very human trait, something that transcends time. "On Wall Street, Pride Signals a Fall" explores the fall in major companies shortly after their success is recognized by the world. These companies develop "a sense of being above the world" after they grace the covers of magazines and stadium scoreboards. Why? The article argues that they reach a point where they have so much confidence they begin to "cut corners" and no perform to their best because they feel they don't have to. Does this differ from Oedipus and Kreon? Oedipus and Kreon both grew so mighty they ignored what was in plain sight. This, very simply put, is where they were tragically flawed. The fallen giants of Wall Street are flawed too, but I think their flaws are less tragic than that of Kreon or Oedipus. In my opinion, their flaw was that they grew so empowered they felt they didn't need to meet some standards. These giants began to hold themselves to different standards than that of their previously prosperous but unknown business began. To me, there is nothing tragic about "boasting", "overpayment" and "pay exceeding 100 million a year". I understand the parallel to "Greek tragedians" in the idea of great powers falling, but that's where it stops for me. My own definition of tragedy as defined above just doesn't seem to apply to these boastful businesses. I feel the hubris relates to tragedy by means of allowing for tragic characters, but I don't feel that all hubristic entities are always those that should be considered tragic. I'm glad I got an idea of hubris and what it means to be hubristic though, because the concept does greatly relate to what I perceive as tragic. "Apples are a fruit but not all fruit are apples". It just so happens though that not all hubristic things, in my opinion, are tragic.

Our perception of the average object of often swayed by our eyes simply not being able to decode what is in front of us. Dan Ariely demonstrated how this is possible through the slides he brought to his presentation. He showed two visual aides that both gave illusions not able to be seen with the naked eye, one being the color of a square on a block.

The colored squares were fixed upon a block at two different sides. At a glance, they look like two different colors, brown and yellow. Yet, that is wrong. He points to them using two large arrows to say look these are the same. Yet again, the illusion of two different colors is still present though he has clearly told us and given us his word they are in fact the same. It is only when he puts a background behind the squares that we see how they are linked, with the same color. Ariely removes the background and once again the illusion is back. We cannot see that they are the same color, even though we have been told it is so, until there is a clear connection drawn to the two. Ariely tells us, gives us all the clues! But we cannot see it unless there is a background given.

Sound familiar? It should. I realized that this tragedy is Oedipus. Ariely is a modern day Tiresias. He's telling us "there's no way for us not to see the illusion", but that it is in fact there. Do we believe him? Perhaps, but it's only until background is given that we can really see it for ourselves. We are Oedipus, and this was his great fault. Oedipus saw two different squares, Laius' murderer and himself as King. To him, they were completely separate entities never to be related at all. It is only until Tiresias gives Oedipus clues and background that he begins to see that maybe they aren't so different at all. This is terrifying. Imagine that we use our eyes, every day, yet we couldn't see the illusion Ariely presented until he fed it to us. This is a personal glimpse into Oedipus' terror on a much smaller scale. He couldn't stand to see himself as Laius' killer and son or husband to his mother. Tiresias warned him though, but really he couldn't face the facts until he saw his tragedy unfold himself.

Seeing that these squares are indeed one is like knowing killer and incestuous husband are one for Oedipus. Dan Ariely is our Tiresias, giving us all the clues to know that two squares are one. It's tragic that we cannot see the similarities in squares because we use our eyes everyday and are so familiar that what they see is correct. Oedipus saw everyday his wife and to him there was nothing out of the ordinary about his life. Oedipus was confronted about the murder of Laius and to him sought out a man he did not know. He saw no reason to think anything of himself until Tiresias pointed it out, just as we has no reason to think the squares were the same color until Ariely noted so. Oedipus couldn't see until there was background, and he saw it for himself. This TED Talk gave me the ability to step into that position, and I know now it must be horrific to come to a realization you couldn't see with your own eyes. Now it seems that though Oedipus saw what Tiresias prophesized, he would now be just as blind to Ariely's illusion as we are.

"Oedipus the King" is a tragic play depicting the ruler of Thebes Oedipus, and his downfall as he uncovered the truth about his life. Sophocles illustrated for us how Oedipus' blindness to his own past and destiny would cause him great turmoil though he was highly regarded through-out his kingdom as a man of great esteem. Oedipus was a man who seemed to have it all, but his need to identify the killer of Laius, the past ruler of Thebes, leads him to discover the horrors of his life. The tragedy is that he is warned at every turn to stop his search but marches forward. In the end, he discovers his wife Jocasta is also his mother and upon a chance encounter he murdered his father Laius which fulfilled a prophecy the King and Queen thought they'd taken care of by killing their son.

Oedipus, enraged, sends for blind prophet Tiresias to hopefully uncover more truth about Laius' death. Sophocles gives us irony in Tiresias' dialogue as he eludes to the truth with lines like "You think I am a fool, but to your parents, the ones who made you, I was wise enough." This use of word play allows for the audience to see what blind Tiresias does, and also allows them to see just how oblivious Oedipus is to Tiresias' hints. Oedipus' parents trusted Tiresias' word and sent their son to die. It's tragic that Oedipus is so enraptured with the notion of discovering the killer he fails to analyze his own life until it is far too late. Oedipus was that son! Those are his parents, Laius and Jocasta! Though Oedipus himself fails to see what he is being warned, the audience picks up on what Tiresias is proclaiming. This foreshadowing gives the tragedy room to grow and lets the audience physically see how the plot thickens now that they have the insight given by the blind prophet.

His marriage to his wife Jocasta takes an incestuous twist as it is revealed that she is also his mother, unbeknownst to Oedipus or Jocasta. This is already alluded to by Tiresias when he says a multitude of things indicating he should question Jocasta's motives. "...[Y]ou have your eyesight, and you do not see how miserable you are, or where you live, or who it is who shares your household." Who shares his household? Immediately the reader knows Tiresias speaks of Jocasta. When Jocasta finally makes the connection to who her spouse is, she commits a tragic death by hanging herself. Jocasta was overwhelmed with herself because she has no idea the horrible act she'd committed. To bed her husband's murderer and her son she'd thought was deceased was not something she'd sought to do, yet it happened all the same. It's tragic she didn't realize what she'd become, mother/wife/grandmother/mother all at once! When Oedipus sees her hanging lifelessly from her noose he gauges out his eyes. This act of self-inflicted pain mirrors Jocasta's suffering, but also has deeper meaning then self-punishment. By blinding himself he is now like Tiresias and can truly see the atrocity that is his life. Things almost come full circle as Oedipus is lead into the square by a small messenger, like Tiresias was by the small boy, to reveal what has been done by all parties involved. This is tragic because it took his entire world to crumble before he could look beyond his own greatness to see the mess of his life.

His down fall could've come at a more gradual pace has he just listened, and the audience can infer what is about to happen which plays further into the idea of audiences taking pleasure in the demise of another. The reader/viewer is on the edge of their seats waiting to see what is in store, further creating the idea of a tragic tale. The audiences perception of what Sophocles wrote is, in my opinion, what adds to the idea of tragedy. One could write a play and call it a comedy, but if an audience doesn't laugh then really is it a comedy at all? The same principle applys here. It takes the audience understanding that this is indeed a tragedy, not a failure, that leads Oedipus to his down fall. Oedipus really was blinded from the beginning. First by his own glory, but in the end he was blinded by his own tragic fate.

The TED Talk we watched really opened my eyes to why tragedy would've been a great source of ancient entertainment. In the TED talk, the speaker shined a new light on tragedies past and how folks' belief systems made them view tragedy differently. By placing misfortunes blame on Gods and other figures of divinity, people of the ancient world viewed those who were placed in situations like poverty or infidelity were not "losers" just people who had lost. Modern society has evolved from this view point though. We now see blame placed entirely on ones self, and not really upon the fates at all. This twists our view of tragic themes like poverty and infedelity. Placing the blame on only ourselves doesn't allow us to view tragedy in the way of those who came before us because we've moved on from the Gods!

Then where is our "fate" and success decided? Ourselves? I tend to think largely no. Though we have to physically do it ourselves, I think that society plays a large role in how we determine our own success. In our time, unless you're moving and shaking, making bank really, you may not be considered to be much. To not achieve, is ultimately to fail. We've drawn such a thin line between our concepts of "failure" and "success" that really there is little room left to be average. Climb high or be lost is the growing trend.

A moment of clarity came to me when I was thinking about this notion, society and success. How does that relate to tragedy? It IS how we define tragedy! We equate whatever society thinking of us as our definition of succeeding. If we are not striving to be a cut throat business exec., society deems us lazy or not reaching our full potential. For example, society is pushing kids to go into math and science fields and if they don't they're automatically failing society's standard of success. Another way of looking at it is something familiar to me, high school grades. I don't get A's in math class, I never have! But I do my best, work my hardest, and eventually pull out a B+ I'm pretty proud of. Some people have looked down on me for not acing my honors level math, but I choose not to let these other people tell me my hard earned B+ isn't success. This relates to tragedy because if society deems your own down fall is a failure, and not tragedy, you aren't pitied you're scorned. By letting the majority at large decide what our success and failures are, we let them limit the way we differ what used to be considered tragic and is now considered failures. In the TED talk the speaker challenged us probe our own notions of success. I'd like to also think that was a way to perhaps explore and reevaluate my views of the modern tragedy in comparison to what was once considered tragic.

I've always seen tragic things a sad happening of different events. The early death of a loved one, a bride left at the alter, a small child left to their own devices because of neglectful parents. This to me is how I categorized tragic events before exploring the idea through a literary lens. Upon further exploration though, I now see there is much more to tragedy than what I has initially thought.

They say that tragedy started with the Greeks, and I suppose you can hold that as a

cursory outline. I'm sure tragic things happened long before tragedy were put into forms of literature. Aristotle seems to be the first to really define dramatic tragedy as "an enactment of a deed that is important and complete, and of [a certain] magnitude, by means of language enriched [with ornaments], each used separately in the different parts [of the play]: it is enacted, not [merely] recited, and through pity and fear it effects relief (catharsis) to such [and similar] emotions." I understand the concept, but to me it's mystifying that people take pleasure in the suffering of others like this. To know that in ancient times this is how people "got their kicks" before TV and radio seems strange. I picture Greeks and Romans with lions at their side laughing and being enthralled with someone playing dead in front of them.

Yet, I can't say I'm not drawn into perhaps what could be considered "modern" tragedy. I come home and watch Law and Order: SVU, Criminal Minds and NCIS. In these crime shows people are often kidnapped, raped, or murdered. Though gruesome in nature, I can't help but be fascinated! I don't know why, it's not like I wish this upon others. Maybe this is the "catharsis" Aristotle references, and why tragedy is an art that's lasted through time.

I'm interested to see what the pieces were going to study have to offer in terms of tragedy. Death? Deception? Or something else outside of the realm of normal? Given what I've learned from today's Wiki-page, I'm hoping we get the opportunity to explore a large range of time so I can see how the idea of tragedy has evolved.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed